Chemistry of Natural Soap Making

A customer who is a middle school science teacher and also dabbles in soap making asked if I could explain the chemistry of soap making in a detailed but simple way.

Of course, I thought what a great idea for a blog.

You do not need to understand the science behind your bar of soap.

However, an in-depth look at the soap-making process may help you understand why a cold-processed, handmade bar of soap is an exceptional choice for your skin.

If you dig deep back to your high school chemistry days, you may remember learning about acid-base reactions. When an acid and a base combine, they neutralize each other and make a salt.

In simple terms, saponification is the name for a chemical reaction between an acid and a base to form a salt called "soap."

I explained the simple version of saponification in our blog titled, Is There Lye In Natural Soap? Won't It Harm My Skin?

Let's Dig Deeper into the Chemistry of Soap Making

Sodium hydroxide is the alkali (base) and the acids are the fatty acids that make up the triglycerides present in oils and butters. When the fatty acid and the sodium hydroxide (lye) combine they neutralize each other and make a salt we call SOAP.

Let's begin by discussing the chemical structure of fats (oils).

On the left-hand side of the graphic you see the backbone of a glycerol molecule. This molecule is always the same in every fat (triglyceride) molecule. Each black “O” in the glycerol molecule represents an oxygen atom. Notice there are 3 of them, each of which is attached to a fatty acid (the zigzag lines on the right).

In the drawing, I show three different looking fatty acids attached to the glycerol molecule. The fatty acids can all be identical or a mix of different types - the only requirement is that there are three of them. This variability allows for a wide range of possible triglyceride combinations, which in turn affects the characteristics of the final bar of soap.

Fats and oils are called triglycerides because there are three (tri) fatty acids joined to a glycerin molecule. Imagine the glycerol molecule like a tree trunk and the fatty acids are its three branches.

Fatty Acids and Soap Making

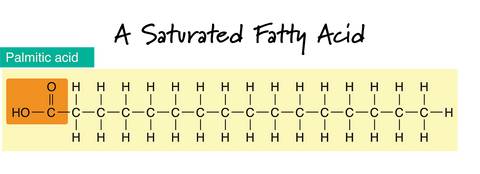

It is difficult to imagine a fatty acid because we can not see it. There are two main types of fatty acids, saturated and unsaturated. You have no doubt heard about these relative to nutrition, and they are extremely important in determining the qualities of a bar of soap.

In the drawing of a Saturated Fatty Acid, the dash "-" lines in between the carbon atoms (C) represent a single bond. Notice that the carbon chain is straight and that there are only single bonds between the carbon atoms. If there are only single bonds between neighboring carbons in the hydrocarbon chain, a fatty acid is said to be saturated.

Saturated fats also tend to be solid at room temperature. This makes sense if you can picture how they would neatly stack together. Fats and oils containing higher levels of saturated fats will add "hardness" properties to a bar of soap. They are usually also the oils responsible for bubbly lather. The four most common saturated fatty acids found in soap-making oils are myristic, lauric, stearic, and palmitic.

Notice in the unsaturated fatty acid that the carbon chain is no longer straight, and now there are double dash lines "=" between some of the carbon atoms. These double dash lines (that look like equal signs) are called "Double Bonds." When the hydrocarbon chain in a fatty acid has at least one double bond, the fatty acid is no longer saturated because it contains fewer hydrogen atoms.

Fats containing a single double bond are called monounsaturated, like olive oil. Fats containing many double bonds are called polyunsaturated, like safflower and sunflower oils.

Unsaturated fats usually come from plant sources, and since their molecules do not compact neatly, they are usually liquid at room temperature. These fatty acids add creaminess to lather and conditioning properties to soap. The four most common unsaturated fatty acids found in soap-making oils are oleic, linoleic, linolenic, and ricinoleic.

Unpacking the Science of Saponification

The word saponification comes from two Latin words "sapo" meaning "soap" and "facere" meaning "to make." This chemical reaction is the foundation of soap making.

As illustrated in the Saponification Reaction graphic, there is one triglyceride (fat) molecule, which is made up of three fatty acids (indicated by the "R" in the green circle).

Since each fatty acid needs to react with one sodium hydroxide (NaOH) molecule, you need 3 molecules of NaOH (lye) for each triglyceride. When making liquid soap, a different base or alkali called Potassium Hydroxide (KOH) is used instead of NaOH.

Although not shown in the diagram, the saponification reaction also yields a bit of water along with the glycerin and soap, but as the soap cures, much of the water evaporates.  The basic equation for saponification can be written as:

The basic equation for saponification can be written as:

Triglyceride (Fat/Oil) + 3 Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH) → Glycerol + 3 Soap Molecules (Sodium Salt of Fatty Acid)

Although water does not appear in the saponification reaction, it plays a crucial role. The sodium hydroxide must be dissolved in a water-based liquid for the reaction to occur. There is no fixed relationship between the number of molecules of water needed, it is simply used to dissolve the sodium hydroxide so that it can react with the oil. While the typical liquid used in most soaps is water, other liquids like milk or juices can be used.

The first part of the soapmaking process begins when the NaOH is dissolved in water, dissociating into sodium ions (Na+) and hydroxide ions (OH-). This reaction is exothermic, meaning it releases heat.

The Results of the Saponification Reaction

Once the sodium hydroxide solution (lye) is added to the fats, the 3 highly reactive (OH) ions from the 3NaOH break the 3 ester bonds in the triglyceride, leading to the formation of one free glycerol molecule (glycerin).

Once the sodium hydroxide solution (lye) is added to the fats, the 3 highly reactive (OH) ions from the 3NaOH break the 3 ester bonds in the triglyceride, leading to the formation of one free glycerol molecule (glycerin).

Meanwhile, each of the 3 sodium (Na) ions pairs up with a fatty acid to form 3 fatty acid salts, essentially 3 molecules of soap.

In simple terms, when we combine fats or oils with sodium hydroxide (lye), they transform into soap and glycerin. Take another look at the Saponification Reaction graphic, and you will notice that one molecule of glycerin and three molecules of soap are formed from each triglyceride.

Side note: You might come across the terms glycerol, glycerin, or glycerine used interchangeably. . Don't worry - they all refer to the same compound, and there is no chemical difference between them. The common name for glycerol is indeed glycerin.

The glycerin produced in every soap-making reaction is always the same. Glycerin, a humectant and a moisturizer, is often extracted from commercial soap to make the bars harder, but all the glycerine goodness remains in handmade soap.

The real magic happens with the three soap molecules, each with its unique fatty acid composition.

This reaction is not limited to one triglyceride molecule, it is happening to every single molecule in a fat/oil mixture.

This reaction is not limited to one triglyceride molecule, it is happening to every single molecule in a fat/oil mixture.

Millions and millions of triglyceride molecules yield millions and millions of soap molecules, each one contributing its distinct properties to the final bar of soap.

At first glance, the saponification reaction seems simple, just mix oils and lye together. But the science is more nuanced.

Each oil is composed of different types of fatty acids in varying percentages. Depending on the types of fatty acids present, the resulting soap will have vastly different properties. This complexity is what makes soap-making a precise science that requires a deep understanding of the ingredients and their interactions.

To create exceptional soaps, a thoughtful blend of oils with diverse fatty acid profiles is essential.

Although there are hundreds of known fatty acids, soap makers primarily need to understand the properties of around eight key ones. The four saturated fatty acids come mainly from oils that are solid at room temperature and include myristic, lauric, palmitic, and stearic acids.

- Myristic acid, found in coconut and palm kernel oils, contributes to hardness, cleansing, and lather.

- Lauric acid, also found in coconut and palm kernel oils, contributes to big bubbles.

- Palmitic acid, found in palm oil and cocoa butter, helps create a hard soap bar with a stable, creamy lather.

- Stearic acid, found in solid butters like shea, mango, and cocoa, is also in palm oil and beef tallow. This acid also helps create a hard soap bar with stable lather.

The four unsaturated fatty acids come from plant oils that are usually liquid at room temperature. They include oleic, linoleic, linolenic and ricinoleic.

- Oleic acid, best known from olive oil but also present in other oils like canola, adds moisturizing and conditioning properties to soap.

- Linoleic acid, found most abundantly in sunflower, safflower, and grapeseed oils, also adds moisturizing and conditioning properties.

- Linolenic acid, found in flaxseed, pomegranate, and some other seed oils, adds moisturizing and conditioning properties.

-

Ricinoleic, found only in castor oil, adds moisturizing qualities to soap. But most importantly, it adds amazing dense, creamy, and bubbly lather. Due to its unique fatty acid make-up, there is truly no other oil quite like it.

Conclusion

Saponification is the result of an acid/base reaction. When an acid and a base combine, they neutralize each other and make a salt. Sodium hydroxide is the alkali (base) and the acids are the fatty acids that make up the triglycerides present in oils and butters.

Once we select the oils and mix them with sodium hydroxide and a liquid, the molecules combine, a chemical reaction occurs, called saponification (pictured below), and a totally different substance is created -- SOAP plus glycerin.

You don't need to be a chemistry expert to use or make soap, but having a deeper understanding of the science behind it can elevate the experience.

You don't need to be a chemistry expert to use or make soap, but having a deeper understanding of the science behind it can elevate the experience.

Just as a skilled chef knows that mastering the art of cooking involves both creativity and a grasp of the underlying food chemistry, a skilled soap maker recognizes the importance of understanding the science of saponification.

While following a recipe can yield decent results, truly exceptional handmade soap requires a thoughtful approach to selecting and balancing the right fats and oils. By grasping the chemistry behind how these ingredients interact with lye, soap makers can craft high-quality bars that nourish and delight the skin.

Now it's time to find the organic soap that's perfect for you.

Is There Lye In Natural Soap? Won't It Harm My Skin?

How Does Natural Soap Create Lather?

How We Make Soap At Chagrin Valley

12 Reasons To Use Natural Soap

Are All Handmade Soaps The Same?